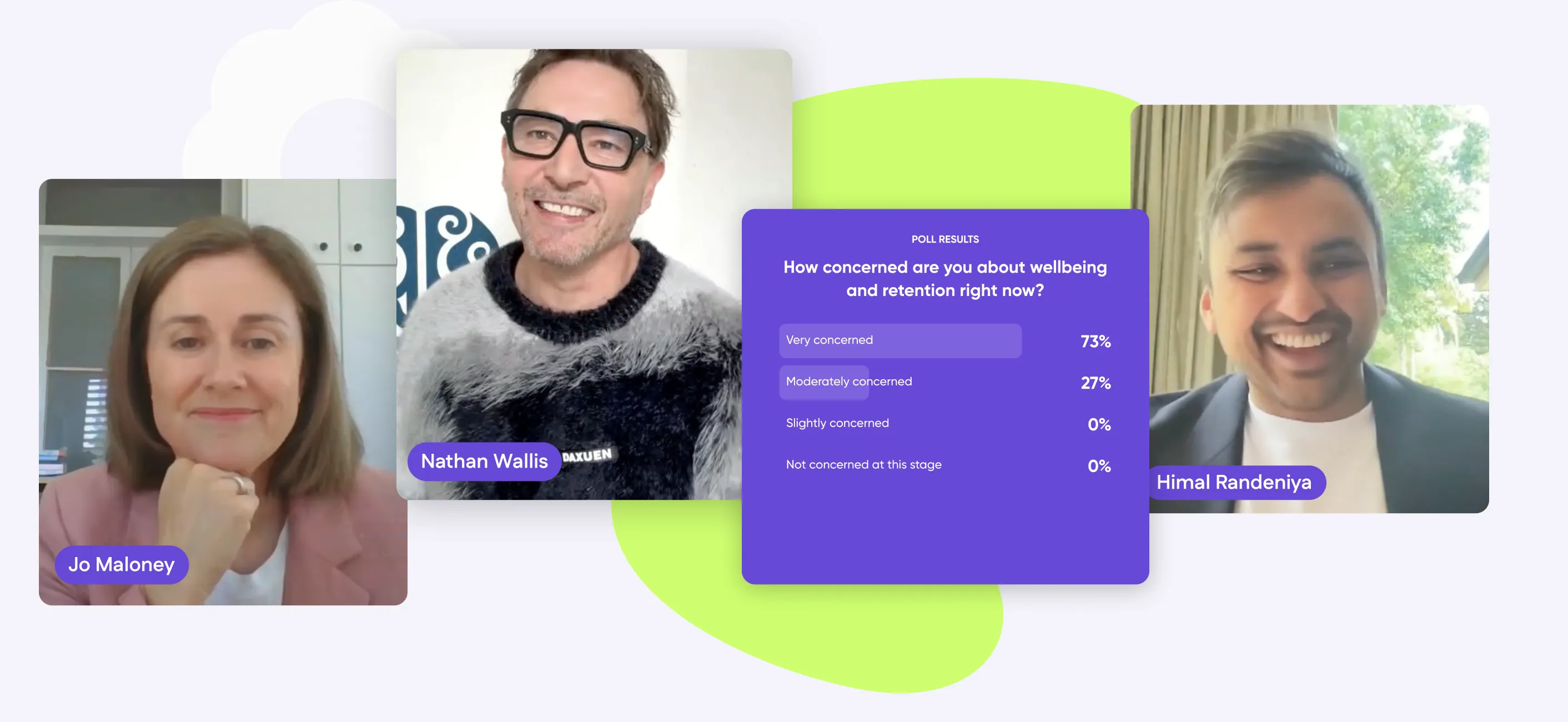

Recently, we had the privilege of sitting down with renowned neuroscience educator Nathan Wallis for an in-depth conversation about brain development in the early years. Nathan, who lectured in Human Development at the University of Canterbury and has delivered over 200 presentations annually across Australia and New Zealand, has a gift for making complex neuroscience accessible and immediately applicable to everyday practice.

What struck us most about our conversation wasn't just the compelling research Nathan shared, but how it validates what many ECE professionals already know intuitively: the work you do in those early years matters profoundly. Here's what we learned that we think will resonate with educators working with young children.

The First 1000 Days: Why This Window Matters

Nathan was clear from the start: "If you want to shape a human being, it's all about the first 1000 days."

"If you want to shape a human being, it's all about the first 1000 days."

Nathan Wallis

The first 1000 days (from conception to around 2.5 years) represents the period when the human brain is working out what sort of brain it's going to need for the rest of its lifespan. Between birth and age three, the brain more than triples in size, growing from less than 400 grams to around 1200 grams. From age three to adulthood? It barely grows at all.

This means that if you're caring for children 0 to 3, especially full-time, you're having a huge impact on the actual architecture of that child's brain. As Nathan put it: "If I'm looking after a child 0 to 3, especially if it's full-time, I'm going to have a huge impact on the actual architecture of that child's brain."

What this means for your practice: The everyday interactions you have with infants and toddlers aren't just keeping them safe and happy in the moment. You're literally shaping the neural foundations that will support all their future learning and development.

It's Not About ABCs. It's About Relationship.

One of the most liberating insights from our conversation was Nathan's clarity on what actually drives brain development in those early years. It's not flashcards. It's not early academics. It's not teaching letters and numbers.

"Language is the major driver of cognition," Nathan explained. But he was quick to clarify what he really means by that. When researchers measure the number of words spoken to a baby, they're not really measuring vocabulary lessons. They're measuring something much more profound: the quality and frequency of genuine partnership between an adult and a child.

"My brain's amazing, your brain's amazing," Nathan told us. "But the really, truly amazing stuff is when your brain and my brain come together. That's where the gold is in neuroscience."

"My brain's amazing, your brain's amazing. But the really, truly amazing stuff is when your brain and my brain come together. That's where the gold is in neuroscience."

Nathan Wallis

The research shows that babies who hear 20,000 words per day (typically from a parent at home) are twice as often in genuine partnership as babies who hear 10,000 words per day. But these numbers aren't targets or checklists. They're simply how researchers measure the quality and frequency of adult-child partnership. It's not about the words themselves. As Nathan emphasised, language is just the measurable proxy for what's really happening: connection, partnership, and relationship.

What this means for your practice: Your conversations with children, your narration of daily activities, your responsive interactions are building their cognitive structures. But even more than that, it's the sense of partnership, the feeling of being truly seen and responded to, that drives brain development.

How to communicate this to families: Help parents understand that it's not about buying educational toys or drilling their child on colours and numbers. It's about being in genuine partnership with their child. Talk, sing, respond, and be present. That's what builds brains.

The Dyadic Relationship: Why One-on-One Matters

Nathan introduced us to a term that might be new to some: the "dyadic relationship." This refers to the one-on-one partnership between a baby and their primary caregiver.

"It takes a village to raise a child," Nathan acknowledged, "but no village hands the baby out of the tent an hour after birth and says, 'There you go, everyone in the village, have a day each with the baby.' It's always been that the village wraps supports around what is essentially a dyadic one-on-one relationship."

Babies are designed to have this primary relationship in their first year. It's how they feel safe enough to build their brain architecture. And here's the important part for ECE educators: if you're caring for a baby for significant hours each day, you become that primary caregiver. Once that transition happens and the baby feels safe with you, your language and connection shape their brain development.

What this means for your practice: Those transition periods when babies are settling in aren't interruptions to your curriculum. They're essential work. Building that secure relationship with each child in your care is the foundation for everything else.

How to communicate this to families: Parents sometimes worry that their baby forming an attachment to you means they're losing something. Help them understand that babies have the capacity for multiple secure attachments, and that their child feeling safe and connected with you actually supports healthy development.

Transitions: When the "Interruption" Is the Curriculum

One of the most practical insights from our conversation came when Nathan addressed something many educators experience: the parent who lingers at drop-off while their child takes time to settle.

"You see early childhood teachers wanting to push the parents out the door and say, 'He'll be fine, he'll be fine,'" Nathan observed. "But neurologically, when the parent stays and it takes longer, it's laying down those foundations much more effectively."

Here's why: separating from a parent is one of the most difficult things a young child has to navigate. When a parent stays and works through that separation with their child, the child is learning to regulate their emotions. They're learning how to deal with difficult things. And that's essential curriculum.

"Don't think of it as an interruption to your curriculum," Nathan encouraged. "Think of it as your curriculum. This is the child learning how to regulate."

"Don't think of it as an interruption to your curriculum. Think of it as your curriculum. This is the child learning how to regulate."

Nathan Wallis

What this means for your practice: Give families the time they need at drop-off, especially during transitions or with new children. Those 10 to 15 minutes of a parent staying while a child settles aren't wasted. They're building the child's capacity for emotional regulation.

How to communicate this to families: Frame those longer goodbyes as a positive thing. Explain that you're working together to teach their child one of the most important skills: how to manage difficult feelings and transitions.

Behaviour as Communication: A Powerful Reframe

Towards the end of our conversation, Nathan and our CEO Himal discussed an approach that resonates deeply with quality ECE practice: treating behaviour as communication.

"All behaviour is communication," Nathan explained. "So you climbing up the wall that you're not allowed to climb up, I wonder if that was trying to tell me something. You're going to treat it as communication, not misbehaviour."

"All behaviour is communication. You're going to treat it as communication, not misbehaviour."

Nathan Wallis

This reframe shifts everything. Instead of asking "How do I stop this behaviour?" we ask "What is this child trying to tell me?"

Maybe they need more physical challenge. Maybe they're overwhelmed. Maybe they don't feel safe. Maybe they need connection. When we treat behaviour as communication, we respond to the underlying need, not just the surface action.

What this means for your practice: When you're faced with challenging behaviour, pause and get curious. What might this child be trying to communicate that they don't have the language or capacity to express otherwise?

How to communicate this to families: When parents ask about their child's behaviour, help them understand this framework. "When Charlie hits, he's usually telling us he's overwhelmed. We're working on helping him recognise that feeling and communicate it." This removes judgement and opens up partnership with families.

The Resiliency Factors Every Educator Should Know

Nathan shared research on the top four resiliency factors that predict positive outcomes for children. While we won't detail all four here, the number one factor is particularly relevant for ECE professionals to understand.

The top resiliency factor is having a parent stay at home in the first year of life. But Nathan was quick to provide crucial context: this research is really about language exposure and connection. Parents at home typically speak more words to their baby because they can give undivided attention.

For ECE educators, this isn't about guilt or suggesting centre-based care has to be second-best. It's about understanding that when you're caring for infants, your role in providing rich language exposure and genuine connection is essential. You're not a substitute. You're a vital partner in that child's development.

This research reflects historical and structural realities, not a judgement on modern families. Quality early learning environments can, and do, provide the rich language, connection, and continuity that support resilience.

The other resiliency factors Nathan highlighted were being bilingual, playing a musical instrument, and having the same teacher for more than one year. That last one particularly stood out to us. Continuity of care matters. When children can stay with the same educator over time, they spend less time re-establishing relationships and more time learning and growing.

What this means for your practice: Advocate for continuity of care models where possible. The relationship you build with a child compounds over time.

What We're Taking Away

Our conversation with Nathan Wallis reinforced something we believe deeply at Mana: the work of early childhood educators is profound and irreplaceable. You're not just supervising children or keeping them safe (though of course you're doing that too). You're shaping the architecture of their brains through thousands of daily interactions.

The science tells us what many of you already know in your bones: it's relationship that drives everything. Not curriculum delivered or boxes ticked. Connection, partnership, presence. That's what builds brains.

When you're changing a nappy and narrating each step, waiting for a response, you're building neural pathways. When you're getting down on the floor and following a toddler's lead in play, you're creating the foundations for lifelong learning. When you're supporting a parent through a difficult drop-off, you're teaching emotional regulation.

This is the profound work of early childhood education.